For those of you who’ve been following my blog for a while, you’ll probably not be surprised to hear that I spend a lot of time thinking about modern morality. If you haven’t been following along but still want to be one of the cool kids, you can check out this or this or this or, if you’re feeling super adventurous, this.

In short, I think that in the modern West the competing moral systems basically boil down to formal Christians struggling against ethical Christians. (You can make a very similar comparison in East Asia between formal and ethical Confucians, incidentally.) Considering I just made those terms up, it’s probably best if we take a paragraph or four to unpack the concepts.

So let’s start with the formal Christians. These are the people most likely to actually identify as Christians. These are the folks who value prayer, going to church and family values. A formal Christian sees the inherent value in smiting the wicked and upholding traditions. These are the partisans of order, of calm, of fighting back against the “fetishists of self-loathing” you’ll find teaching humanities classes at American universities and the “unwashed heathens” protesting in front of your local investment bank.

The symbols and forms of Christianity as used by people who are absolutely not poor fishermen.

The formal Christian’s strengths are an innate regard for self and the belief that power is good. Almost anything you see will have been built by formal Christians, the cars and museums and the empires will all have sprung from people of the establishment. Indeed the formal Christian’s primary ethical belief is that “I am good and the things associated with me are good.”

I call these people formal Christians because they are about symbols and rituals. They are the sort of establishment Christians that only became possible in the shadow of Emperor Constantine. They are the Christians who wear power suits and guild the cross. The formal aspects of Christianity, that is to say, the symbols, have more or less completely replaced Jesus’ and the Apostle Paul’s early Christian ethics, which brings us to the ethical Christians.

That the strong might know the suffering of the weak.

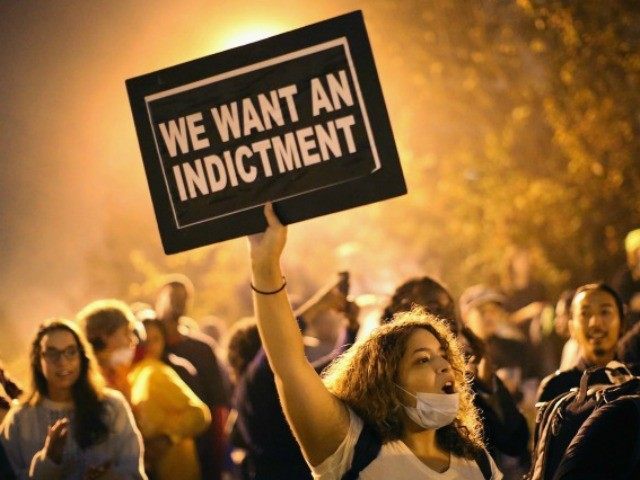

The ethical Christian opposes the formal Christian in a fashion nearly identical to the way early Christians opposed Roman paganism. The ethical Christian, just like Christ, sees little but corruption and rot in the established powers. The ethical Christian, just like Paul, hates his natural desire for domination, despises the instinct for status, opposes the animal’s drive for violence. The formal Christian, filled with guilt and shame, turns her pity towards the poor and outcast and strange. She raises her fists to heaven and burns at the injustice of it all. The ethical Christian says of himself “I’m the 99%,” he opposes “the man” and worships at the altars and shrines of the gloriously martyred.

Where the formal Christian builds the ethical Christian tears down. Imperialism fell at the hands of ethical Christians, as did the Tzars, Jim Crow and the unbelievers destroyed by ISIS. Wherever you see power challenged and the mighty humbled, you will find ethical Christians.

Where the formal Christian bases his ethics on the belief in his own innate goodness, the ethical Christian basically despises her anti-social desires. Where the formal Christian believes in her place among a glorious lineage, the ethical Christian believes in nothing so much as the need for rebirth.

It has perhaps not escaped your notice that the ethical Christian is very unlikely to call himself a Christian. Indeed, I would nominate Karl Marx and Richard Dawkins as some of the most representative ethical Christians of the last couple centuries. However, while these people go to great lengths to reject the forms of Christianity, the crosses and prayers and family values, they cling to the practical ethics of Christ like barnacles to a rusty tanker.

Why Jesus has nothing to do with formal Christians but everything to do with Marx: “Blessed be ye poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God. Blessed are ye that hunger now, for ye shall be filled. Blessed are ye that weep now, for ye shall laugh. Blessed are ye when men shall hate you, and when they shall separate you from their company, and shall reproach you and cast out your name as evil, for the Son of Man’s sake. Rejoice ye in that day and leap for joy, for behold, your reward is great in Heaven; for in like manner did their fathers unto the prophets. But woe unto you that are rich, for ye have received your consolation. Woe unto you that are full, for ye shall hunger. Woe unto you that laugh now, for ye shall mourn and weep. Woe unto you when all men shall speak well of you, for so did their fathers to the false prophets.” Luke 6:20-26

This brings me to an examination of empire and the ways both types of Christian interact with greatness. Empires all fall. It doesn’t matter how much they build, how glorious their achievements or how clever their founders. Rome still burns, Alexander still dies, the Khans still can’t hold it together. Why?

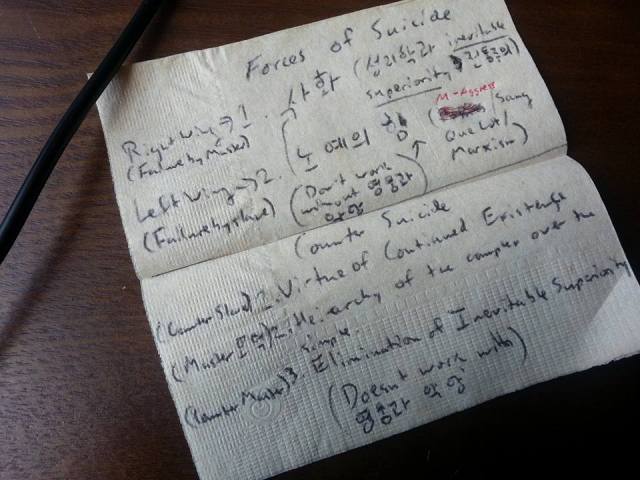

Shouldn’t these glorious things, possessed of all imaginable advantages, persist against those whom they’ve vanquished? Perhaps it is luck, perhaps holding an empire together is just really hard and given enough shots, a weaker opponent will eventually get lucky. I’m sure this is part of the reason, but I don’t think it’s all. I think these empires committed suicide.

Some died in ways you’d expect from the formal Christians. The rulers of the late Roman Empire, for example, believed in their own goodness so much that they thought it was simply inevitable that they and their progeny would maintain power no matter what. They were just so damned cool that they could pass their property on to their kids, they could shuffle off dirty work like soldiering and administering onto mercenaries and plebeians – people with no hope of advancement within the establishment. After all, they were so good it’s just kind of inevitable they and their progeny would continue to reign in perpetuity.

They were what I call “inevitably superior.” They were not superior because they defeated the Gauls in single combat, they were not superior because they’d invented the phalanx and they were not superior because they’d subdued the steppe tribes – they were superior just because … well, umm … reasons and stuff.

Imagine this dynamic as it appears in a romance novel or princess story. Whether we’re talking about Jasmine or Elsa or Pocahontas, everybody in the story agrees that the princess just automatically deserves to be adored, deserves to be listened to and deserves deference. These stories are so popular because they represent the fulfillment of a fantasy where you, the audience, gets to imagine just being that princess. No hard work, no overcoming, no risk – you are simply rewarded for existing. Whenever you find a social structure with multi-generational dynasties – I’m looking at you House of Windsor, House of Bush and House of Park – you are seeing this wish-fulfillment princess story taken literally.

The problem with the inevitable superiority fantasy is that people aren’t automatically special, regardless of from which sacred womb they emerge. Being the daughter of a great man doesn’t make you destined for greatness, it doesn’t make you anything except very likely inferior to your dad.

The other problem is that human beings are products of their histories. If your history includes doing awesome things because you had to climb the social ladder, you are going to be well prepared to continue doing awesome things when you achieve power. There is no reason to doubt Julius Caesar’s competence, for example. If your history is just basically being born, the probability you can do anything useful is just a crap-shoot. We have no idea if Chelsea Clinton would be a good president because she’s not built up the history of earning power.

But “useless” is such a strong word.

And thus these formal Christians, these believers in the inevitable superiority fantasy, tend to grow weaker with each generation. The great conqueror gives way to a pretty good son who participated in the conquest. He gives way to a bumbling but well meaning grandson who is pretty good at hunting who then gives way to a great grandson who’s greatest skill is tormenting the concubines. Raise your hand if you’ve heard this story before.

If we’re lucky, this just collapses in on itself. The (mercifully) impotent British waste of tax money royal family is probably the best case scenario. If we’re not lucky, the dynastic classes decide that the best way to ensure the safety of their inevitable superiority fantasy is to kill off all the people who have, you know, actual ability. The literati purges from 16th century Korea, the White Terror in Falangist Spain or the fenshu kengru of Qin Dynasty China are examples of this in action.

Even this, though, is better than what happens to empires controlled by the resentful, the self-hating, the ethically Christian. The ethically Christian, driven by resentment towards the powerful, are at once driven to tear down the edifices that oppress them and unable to build anything new. Death comes swiftly at their hands as they kill the mighty, destroy the structures and lay low the institutions. They are the Arab Spring, they are the French Revolution, they are freed slaves in Libya and they are the Bolsheviks before the Bolsheviks became the new establishment.

Being driven by a horror-of-self, the ethical Christian is essentially reactionary – their decisions are always in reference to something the formal Christian has already done. The ethical Christians can destroy that which corrupts but destruction is all they can do. They can murder Qaddafi but they can’t govern at all. They can wipe out the Bourbons but they can’t reconcile with other revolutionaries of even slightly different world-view. They can throw off the masters, but they can create no alternative to slavery. Ethical Christians are the social equivalent of wild fires or earthquakes.

This all brings me to a problem. I’m really sick of Christian ethics. I’m tired of the corruption and decadence of formal Christians who think they and their progeny can do no wrong. Self-hating ethical Christians, wallowing in pity and nihilism, kind of make me want to vomit. There’s got to be a better way.

Stay tuned for part two, where I explore what I think that better way is.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider buying the author’s novel.

http://www.amazon.com/The-Blackguard-Ben-Garrido/dp/1939051746

For customers living in East Asia.

Interesting post, as always. I’m reminded of this SMBC: http://www.smbc-comics.com/index.php?id=3246#comic

I think the dichotomy you paint boils down to one between cultural morality and societal laws. In almost every society, there’s a difference. Some of it is due to whichever faction of the culture currently holds power, some due to the fact that it can take a while for laws to catch up with evolving cultural mores, but a good portion is that while cultural mores can be idealistic, societal laws need to be pragmatic, at least to some degree.

Of course, there are people who can’t tolerate any compromise of their ideals for logistical practicalities, but such people have never been very good at acquiring or holding onto power. Which is probably why most revolutions, which tends to be when such people get power, usually go bad. (The ones that don’t are usually a “revolution” in name only.)

But just because someone is pragmatic, doesn’t mean that they’re not idealistic. It might mean that of course, but it also could mean they’ve just learned to temper their idealism in order to make actual progress.

Hey Mike,

Thanks for the comment. I think you’re right about the pragmatism vs. idealism thing. Part two of this is going to be my attempt to reconcile ideals (which are usually based on some sort of moral absolutism) with pragmatics (which is usually based in a type of moral relativism).

Because I agree, I think the best word for that pragmatist with no ideals is “nihilist” and I don’t think anybody really wants to go there.

I think I’m going to have to read this over a few more times.

I hope that’s fruitful, and that I’m not wasting your time! 😉

Short version, the people I’m calling formal Christians are roughly analogous to the “establishment” as we understand it in the West.

The people I’m calling ethical Christians are roughly analogous to anti-establishment groups as we’d understand them.

The reason I’m calling them all Christians is that I think you can trace the formal Christian value system to the Church post Constantine and I think you can pretty neatly describe the ethical Christians as the direct descendants of Christ and especially Paul.

Bring on part two. Following is an excerpt from my poetry book, “A Mixed Bag.”

THEOLOGICAL ENTROPY

First there was the Buddha.

Five centuries passed

And then came The Christ.

Another five hundred years

And Mohammed crossed the stage.

And entropic descent

From the pinnacle toward the abyss.

Is this book available?

Thanks, I’ll check it out.

Ben, I certainly don’t write about cars but I do find it curious that we overlap so closely on certain themes. Here’s my take on what I understand this post to be about:

I have no idea why you want to confusingly call both sides to this equation Christians. What you are describing is essentially a power struggle between the haves and the have nots. The State certainly uses all tools at its disposal to retain and increase its power. Those tools might include appealing to a left wing Christian ethic but it might also include appealing to a right wing nationalist ethic. Unfortunately pseudo-scientific Marxist class analysis can’t help us, but there is an earlier and more valuable tradition of class theory, based on the work of classical liberals such as Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, and Augustin Thierry that can.

These theorists recognized that it was not just workers who created value but also anyone who participates in voluntary exchange, including the owners of capital. Absent intervention by the State there is no exploitation. But class warfare does take place when the State interferes in voluntary exchange, creating a conflict between producers, and the parasitical political classes. Or, to quote the view of the later classical liberal John Bright, class warfare is a clash between the tax-payers and “tax-eaters”.

As I describe in my post, resistance can take many forms. Sometimes it takes the form of “ethical Christianity”, as you describe it, but sometimes it takes other forms, some as apparently innocuous as spreading jokes, foot shuffling or working slowly. For some reason you privilege “ethical Christianity” over every other form of resistance.

Hey Malcolm,

Yes, I had noticed about the shared themes. 😉

I characterized everybody as essentially ethically Christian and formally Christian mostly because of my reading of Nietzsche. http://rafal.io/nietzsche-slave-morality.html I didn’t want to say slaves and masters because I think that has connotations today that it didn’t have in 1883 and also because I think my conception is a little bit different from his. I also borrow his distinction between bad and evil.

For Nietzsche, being poor or weak made you a slave. Being a member of the nobility (I don’t actually like this word, but I can’t think of a better term in English – I’d like to call it “yangban” after the Korean word but nobody would know what that means) made you a master. I don’t think this is automatically true.

Many poor people are Nietzschean slaves, but many of them have master beliefs even when those beliefs harm them personally. There are lots of pro-establishment poor people, for example. There are gang leaders, impoverished artists, neighborhood leaders and even schoolyard bullies. These are the folks I’m calling formal Christians because I consider them the heirs of post-Constantine Christianity.

Further, many rich or powerful people are Nietzschean masters, but not all of them. You can be resentful, reactionary and feeling oppressed from the heights of your trust fund and hilltop mansion. These are the folks I’m calling ethical Christians because I consider them the heirs of Jesus and Paul.

For me, spreading jokes, foot shuffling and working slowly would just be types of ethical Christianity.

Reading your View From the Top article, I get the feeling you don’t think “haves” and “have nots” are inevitable. I think I disagree with you here since while wealth is not zero sum, power is. That’s important because in my reading of history you don’t find a decrease of struggling when societies become richer. Even when everybody has a chicken in the pot and a car in the driveway, folks still struggle for power.